One of my first forays into exploring why I should consider a more student-centered classroom occurred in my AP English Language and Composition class, now more than 10 years ago. After handing out an assignment, which was a research paper, a student asked, “Okay, but what am I supposed to do in this paper?” It opened my eyes to reconsidering the pedagogical basis of my classroom, namely how I framed learning and instruction.

Handing out an assignment requires many assumptions on my part, including the idea that the assignment would be an accurate reflection of student learning. However, I discovered that it may actually reflect what I taught instead of what the student learned.

This shift in focus from me to the student is what constitutes student-centered learning. In fact, I frequently say, “The person doing the work is the person doing the learning.” The book Information Literacy and Information Skills Instruction quotes John Dewey as positing that learning is something the individual does (Thomas, 2020).

This shift in focus from me to the student is what constitutes student-centered learning. In fact, I frequently say, “The person doing the work is the person doing the learning.” The book Information Literacy and Information Skills Instruction quotes John Dewey as positing that learning is something the individual does (Thomas, 2020).

Many educational organizations’ standards call for developing active learners. The International Society for Technology in Education strives to develop students as knowledge constructors and empowered learners. The Common Core State Standards focus on developing college- and career-ready students who demonstrate independence and are open-minded and engaged. The National School Library Standards begin with Inquire as a Shared Foundation, espousing the belief that “learners benefit from engaging in a structured inquiry-based research process in which they may struggle through questioning, reformulating, failing, rethinking problems, and deciding between solutions. Learners grow each time they iteratively question, create, share, and reflect on new knowledge; natural curiosity is sparked by means of this sustained inquiry cycle” (AASL, 2018, p. 70).

Constructivism

If we are to consider learning as an active process, we will naturally be drawn to principles of constructivism, which allow teachers to design educational opportunities for students to construct their own knowledge. Constructivism emphasizes the importance of students’ prior knowledge and the opportunity to develop their own perspectives on topics as they apply learning to the real world. Moreover, the learning needs to make sense at the time of learning in order to create meaning for the student (Thomas, 2020). Much emphasis is placed on how students move through the process of learning rather than just the end product or assessment (Thomas, 2020).

Because of the social nature of teaching and learning, considering constructivism calls “on teachers to rethink their roles in the classroom and to implement models for instructional delivery in order to accommodate this understanding of how learning occurs” (Thomas, 2020, p. 79).

Contemporary barriers to implementing student-centered learning primarily include standardized testing and standardized teaching. But another barrier includes our own assumptions, biases, and beliefs about the learning process. Student-centered learning does not mean teachers do not have a role to play in the learning process or that the classroom will become disorganized and difficult to manage.

How to Implement Guided Inquiry Design and Inquiry-Based Learning in the Classroom

When considering how to structure constructivism (or student-centered learning) in a classroom, inquiry-based learning is a research-based approach to classroom structure ensuring active learners. Guided Inquiry Design (Kuhlthau, Carol C., Leslie K. Maniotes, & Ann K. Caspari., 2015) establishes such a framework, grounded in research. Students move through the information search process recursively, adjusting their focus and information searches depending on the identified information need. This information need arises after much time spent exploring resources and topics, activating the Third Space, a merging of “students’ personal and cultural out-of-school experience and knowledge and ways of being” with “official curricular knowledge and school ways of knowing and being” (Kuhlthau, et al., 2015, pp. 25–26). When students choose their own learning contexts, they can “construct new worldviews rather than having to take on the teacher’s perspective or those mandated by the curriculum or textbook” (Kuhlthau, et al., 2015, p. 27).

Guided Inquiry Design and inquiry-based learning in general can be implemented by any grade level or content area teacher—yes, it’s possible! Consider some examples I share below to help spark some ideas for rethinking not necessarily your content but a more student-centered approach to teaching and learning.

Examples from My School Library

Back in 2015, some students I talked to mentioned to me that they were being approached by strangers in public. After doing some initial searching on the internet, I discovered that my area of the state (South Carolina) is actually becoming a target area for human trafficking. The state has even established a task force to combat this problem. After doing more searching, I discovered a local organization, SWITCH, which helps to rehabilitate victims of human trafficking. I arranged for SWITCH to present sessions at my school and teachers signed up their classes to attend a session. For some classes, I used this visit to start an inquiry unit on issues related to human trafficking.

I won a grant from the local Junior League for a project entitled “When People Become Pawns: investigating social injustice through selected contemporary literature.” After hearing from SWITCH, students chose a young adult fiction book which featured a topic related to human trafficking and engaged in a project exploring how authors use fiction to bring awareness to social issues.

Part of this project required students to utilize databases to explore information about the issue of social justice represented by their book choice. This approach provided meaningful context for students to practice information literacy and critical-thinking skills but also gave them some freedom of choice based on their own interests. I was able to tailor instruction directly to the needs of individual students at the exact time they needed that additional learning.

In a later iteration of this unit, I embraced student-centered instruction through inquiry-based learning more thoroughly. I knew I wanted students to choose their own topics related to social justice, conduct research, read a fiction book representing that issue, and write a letter to an organization or legislator to take action. To reach these goals, students did not have to complete the same work at the same time as in a traditional teacher-centered classroom. Instead of beginning by distributing an assignment, I introduced the concept of social justice as a unit theme. Indeed, one of the first times I tried this assignment, students asked me the meaning of social justice, which showed me that I needed to rethink my teaching approach and provide some meaningful context.

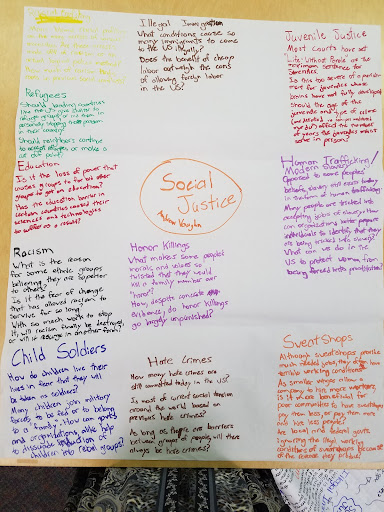

As one of the first steps in an inquiry-based learning unit, I gave students time to explore by widening the topic possibilities. In the picture below, you can see the work of one student. I created stations to represent various examples of social justice: refugees, education, juvenile justice, human trafficking, etc. At each station, I curated a variety of information sources: database articles, images, documentary clips, books, and more. Students had time to move through each station, and their assignment was to create questions about each topic. They were given the opportunity to find their own topics beyond the ones I had curated to spark their interest and curiosity.

Databases are an important resource when implementing this form of student-centered learning. As part of the next steps in this unit, I directed students toward exploring information in databases in order to begin the process of narrowing down their interests and eventually selecting a topic. For example, if a student had no previous knowledge of human trafficking, they could search for more information in the Modern World History database. They would subsequently discover that many countries throughout the world suffer human rights abuses, which would naturally lead them to narrowing down their topic geographically (as one possibility).

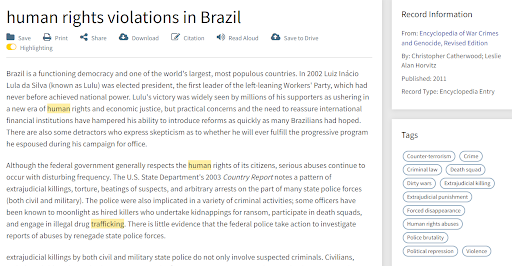

Say a student clicked on the article to learn more about human rights violations in Brazil. They can use the Tags sidebar to learn more vocabulary related to the topic. These terms might help broaden or narrow their topic selection; furthermore, it will guide them to learn even more examples of social justice, such as modern slavery, police brutality, and political repression.

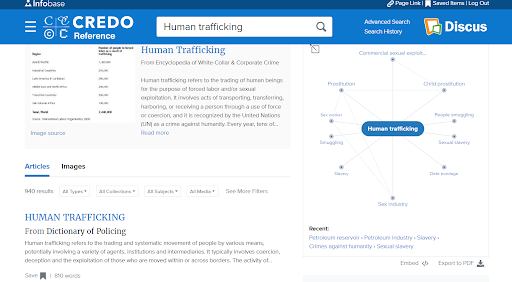

Another effective database to utilize in this unit is Credo Reference. Students can begin with a broad topic such as human trafficking and utilize the Mind Map to discover more topics and vocabulary words.

It’s easy to see through this example how student-centered learning is a more effective teaching and learning strategy because students are able to construct their own meaning through their own active searching. Sure, I could have just given them a list of potential topics on an assignment sheet, but building their own meaning through discovery established a more personal connection to the information.

Student-centered learning does not mean students only study topics they are personally interested in; rather, the instructional design of the curriculum allows for student exploration in order to spark curiosity and questioning, and databases can play a key role in this design.

See also:

- FREE webinar: Differentiated Learning: Strategies to Tailor Instruction to Students’ Needs Using Databases

- Differentiated Learning: How Databases Can Help

- Database Instruction 101: Taking Students Beyond Google

- Defending Intellectual Freedom with Educational Opportunities

References

American Association of School Librarians. (2018). National School Library Standards for Learners, School Librarians, and School Libraries. ALA Editions.

Gregory, Jamie. (2018). The Information Literate Student: Embedding Information Literacy across Disciplines with Guided Inquiry. Teacher Librarian, 45(5), 27–34.

Kuhlthau, Carol C., Leslie K. Maniotes, and Ann K. Caspari. (2015). Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century. California: Libraries Unlimited.

Thomas, Nancy Pickering et al. (2020). Information Literacy and Information Skills Instruction: New Directions for School Libraries (4th ed.). Libraries Unlimited.