Children’s library programs are among the most vibrant and beloved library services. They connect kids and families; support literacy, academic achievement, and career exploration; and help close opportunity gaps—plus, they’re fun! To make sure all children can benefit from library programs, librarians need and want to make our youth programs highly inclusive. What steps can librarians take to help all kids and families feel welcome and included?

Center Youth Voice

One of the most impactful ways to make programming for youth as inclusive as possible is to engage the young people themselves in making decisions. This helps ensure programs are responsive to the cultures, identities, abilities, and experiences of youth in your community. To maximize inclusion, seek out ways to center youth voice that are appropriate and helpful for children’s age and the context.

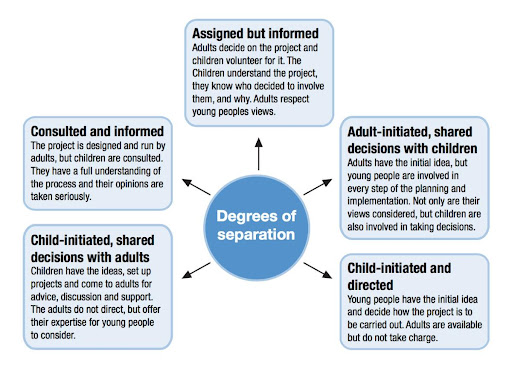

What does it mean to center youth voice? A seminal model for understanding how youth can meaningfully participate in programming decisions is Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship (1992). It has since been reimagined by other scholars, including a hub-and-spoke model created by Phil Treseder in his 1997 book Empowering Children & Young People (see figure).

At the level of “assigned but informed,” if you offer children a program with predetermined steps or goals, you can still encourage inclusion by offering them clear information, letting them ask questions, and giving them choices. For a higher level of participation, you might ask children about what programs they would like you to offer. For the most involvement, adults and children can share the decisions about what programs to offer and how. Or children can initiate and lead the program, with adult support available. There is no one “right” participation level; what you decide to use will depend on the age of the children and the context of the program.

What does centering youth voice look like in practice? To maximize inclusion, librarians should think about how to offer children agency and decision-making in each program. Below are two examples of possible ways to create practical opportunities to meaningfully include both younger and older children.

For Young Children: Process-Oriented, Open-Ended Crafts

Craft projects are a mainstay of young children’s programming. When offering an art or craft activity, librarians should try to provide options that are process-oriented and open-ended. This model stands in contrast to product-oriented art, where the outcome is predetermined. (If you can provide a sample for children to imitate, then you are probably offering a product-oriented craft.)

Especially when librarians want to offer a craft that fits in with a theme, it can be tempting to offer a product-oriented option. For example, we might offer a story time about elephants, then have the children make a set of elephant ears from pre-cut pieces; or we might want to offer a craft program that matches a summer reading theme. Yet children whose abilities do not align well with a product-oriented craft can feel frustrated and inadequate. They may compare their results to the librarian’s example or other children’s work and conclude that theirs is wrong or bad. They focus more on getting it “right” and pleasing the adults than on exploring and enjoying their own creative skills.

In process-oriented arts and crafts, there are many possible endpoints and many creative ways to reach them. Children decide how to experience the project. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) suggests ideas such as painting with unusual tools like toothbrushes or potato mashers; creating spin or squirt bottle art; making collages; weaving or beading without a pre-set pattern provided; or working with clay or sculpting dough. When the project is open-ended, all children can engage at the level of their ability and interest. No child is compared to another, or to the teacher. Every child’s unique creativity and skills are engaged and valued.

For Older Children and Teens: Librarian Structure, Kid Content

Older children can begin to take ownership of the programs they want to attend. The librarian’s role is to provide a structure that offers boundaries and resources, then to support youth in making content decisions. For example, a library might host a middle school zine program. The librarian would provide art supplies and perhaps a sampling of zines or books about them. During the program, the librarian would guide the participants through deciding on their own topic, writing their own articles, creating their own artwork, and editing together the final product. The San Diego County Library offers one example of how to run a youth zine workshop.

Does the library have a teen advisory board (TAB) or teen interns or volunteers? Teens can plan and deliver their own programs, within reasonable guidelines set by a librarian. For example, the King County Library System hosted a series of Teen Voices Summits. Librarians led the teens through a participatory process to determine what topics they wanted to learn about or discuss in their programs. Teens then took the lead in planning and running the event, with ongoing oversight and support from librarians. At the first event, 145 teens came together to talk about topics important to them like bullying, racial equity, and mental health. Youth can even take the lead in marketing their programs, as with the teens at Longwood Public Library who created promotional TikToks for the library with adult support and guidance.

Make Programs Accessible

Centering youth voice is a powerful way to make program content more inclusive. But that content can only reach youth able to access the programs. The librarian is responsible for ensuring accessibility across many dimensions. How will children of all abilities and disabilities be able to participate?

Consider Physical Accessibility

If the program is virtual or includes digital elements, provide captioning and sign language interpretation. If the program is in person, look for spaces that are accessible for children using wheelchairs or mobility aids. If possible, offer programs in rooms equipped with hearing loops. Have a microphone present and make sure presenters use it, so participants who require amplification do not need to publicly identify themselves. In any format, are programs offered at times and locations so that families with working parents can attend?

Accessibility is not only about the program itself. For example, check that users of screen readers can find out about the program, register if needed, and access any preparation or follow-up resources. How easily navigable is your website, online event calendar, and registration system? For a program to be truly accessible, children and their families need to be able to access information about the program without undue barriers.

Create Space for Neurodiversity

Some children may have trouble engaging with a program in a crowded, loud, or highly stimulating environment. Consider ways to help all children address their sensory needs. For example, you might set up a sensory corner in a different part of the room, equipped with a mat, pillows, or beanbag chair; a weighted blanket; earmuffs; and/or plushy stuffed animals and fidget toys. Children who need a break can visit the corner, then return to the program when they are ready.

In addition, libraries might also consider offering programs that are specifically designated sensory-friendly. These might involve smaller groups or less crowded times at the library and lower lighting and sound levels. The library might send parents details or photographs of the activity beforehand, so they can help their child prepare.

In any program, children may need to temporarily disengage for a variety of reasons. To help everyone feel welcome, let families know up front that it is okay for children to to look away, move around, or take breaks as they choose.

Conclusion

When we work to make children’s programs more inclusive, youth and families of all backgrounds can enjoy their benefits. Centering youth voice in various ways makes library programs more inclusive by allowing them to be shaped by the cultures, identities, abilities, and experiences of children in the community. Emphasizing accessibility across multiple dimensions helps ensure that all families can attend, feel welcome, and be part of the community. Inclusive, youth-centered, accessible programs uplift, engage, and empower our children, helping all families and communities thrive.

See also:

- Looking for kid-safe, advertisement-free streaming media for children? Check out Just for Kids, which features the educational videos children want to watch—Sesame Street, The Electric Company, and so much more—plus songs, games, and other interactives that are sure to entertain, educate, and inspire young patrons. Try it today!

- FREE infographic: 4 Strategies to Support Digital Equity in Your Community

- FREE webinar: Kids’ Reference Roundup—Facts, Stats & Images for Homework Help

- How Libraries Can Access Funding from the Digital Equity Act