November is Native American Heritage Month, a time to celebrate the rich histories, diverse cultures, and important contributions of America’s first peoples, as well as a time to bring awareness to the historic political, religious, social, economic, and legal struggles Native Americans continue to navigate. As Americans, it’s a great time to examine our pledge to maintain meaningful partnerships with Tribal Nations, renew our commitment to our nation-to-nation relationships, and continue to work toward ensuring every community has a future they deserve.

What Is the Bureau of Indian Affairs?

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is one of the oldest federal agencies in the U.S., with roots tracing back to the Committee on Indian Affairs established by Congress in 1775. It was originally headed by Benjamin Franklin. The primary mission of this early commission was to negotiate treaties with Native Americans to obtain their neutrality during the American Revolutionary War and oversee trade and treaty relations with various indigenous peoples. In 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was officially established by then Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. It continues to be an important federal agency and has undergone many dramatic changes since its establishment 198 years ago.

The BIA remained within the War Department until 1849, when Congress transferred the agency to the Department of the Interior. From its earliest day, the BIA has been a controversial agency with its mission and motives being challenged along with being accused of abuse, mismanagement, and corruption. The bureau has worked on improving its image, increasing the number of Native Americans working for the agency, and focusing on the services it provides and the resources available for federally recognized Native Tribes in order to enhance quality of life. Today the bureau provides services to nearly two million American Indians and Alaska Natives, and the 574 federally recognized Tribes in the United States.

What Is a Federally Recognized Tribe?

The U.S. government officially recognizes 574 Indian Tribes in the contiguous 48 states and Alaska. Federally recognized Tribes are sovereign nations exercising government-to-government relations with the United States. Hundreds of Tribal nations ceded millions of acres of land that made the United States what it is today. In return, they received the guarantee of ongoing sovereignty (self-government) on their own lands. The U.S. Constitution recognizes that Tribal Nations are sovereign governments and have the both the immunities and privileges available to federally recognized Indian Tribes. Federally recognized Tribes have what is a called a trust relationship with the government and are eligible for funding and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, either directly or through contracts, grants, or compacts. An essential aspect of tribal sovereignty is also tribal sovereign immunity—immunity from lawsuits in federal, state, and tribal courts. Under federal law, an Indian Tribe has immunity, not only from liability, but also from suit.

Today, tribal governments maintain the power to determine their own governance structures, pass laws, and enforce laws through police departments and tribal courts. According to the National Congress of American Indians, Tribal governments exercise jurisdiction over lands that would make Indian Country the fourth largest state in the nation.

Native American Assimilation and Boarding Schools

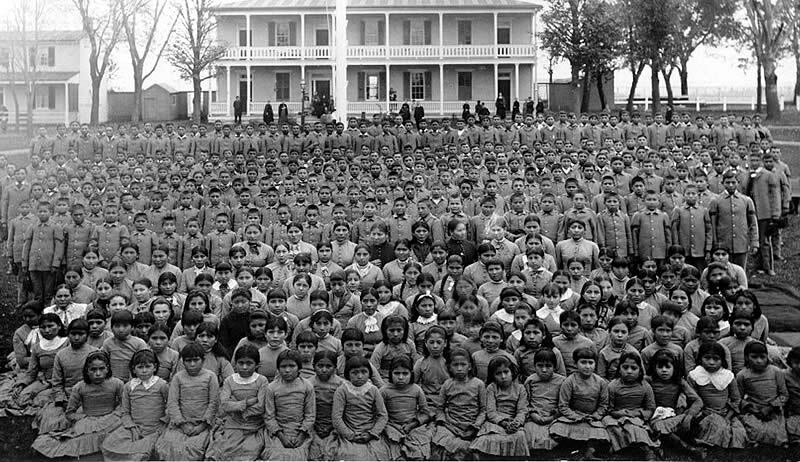

The Native American assimilation era first began in 1819, when the U.S. Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act. The act encouraged American education to be provided to Native Americans to enforce the “civilization process.” The passing of this act eventually led to the creation of federally funded Native American boarding schools and initiated the beginning of the Indian boarding school era. This era ran from 1860 until 1978. Approximately 357 boarding schools operated across 30 states and housed more than 60,000 native children. A third of these boarding schools were operated by Christian missionaries as well as members of the federal government.

Attending a boarding school was made mandatory by the U.S. government regardless of whether or not Native families gave their consent. As soon as the children arrived at the school, they were given Anglo-American names, bathed in kerosene, given military-style clothing, and their hair would be shaved off for the boys and cut into short bob styles for girls. Education focused on making Native students marketable in American society. Male students were taught to perform manual labor such as blacksmithing, shoemaking, and farming amongst other trades. Female students were taught to cook, clean, sew, do laundry, and care for farm animals. Standard academic subjects like reading, writing, math, history, and art were also taught; however, American beliefs and values were emphasized.

Native students were not allowed to speak in their Native languages. They were only allowed to speak English regardless of their understanding of the language and would face punishment if they didn’t. Discipline was severe. Punishments included privilege restrictions, diet restrictions, threats of corporal punishment, and even confinement. Many times, Native students were neglected and faced many forms of abuse including physical, sexual, cultural, and spiritual.

There have been long-term, multigenerational effects of these boarding schools. According to the Indigenous Foundation, Native youth still face several challenges within the American education system. They rarely have access to curricula that are culturally relevant to them and experience difficulties in the classroom at alarming rates. Reports given by the Kids Count Data Center and The National Violent Death Reporting System indicate several issues within Native youth communities:

- 1.2 times more likely to be behind in 4th-grade reading and 8th-grade math

- 1.4 times more likely to be suspended from school

- 1.5 times more likely to die in a homicide or suicide

- 1.7 times more likely to experience two or more adverse childhood experiences

- 1.8 times more likely to attend a high-poverty school

- 2 times more likely to drop out of high school

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report

Although we have come a long way, we still have a long way to go. The number of Native Americans who are elected to U.S. federal government positions continues to increase. On March 15, 2021, Secretary Deb Haaland made history when she became the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, being named the 54th Secretary of the Interior. She is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and a 35th generation New Mexican. On June 22, 2021, she announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, directing the Department of the Interior to undertake an investigation of the loss of human life and lasting consequences of the Federal Indian boarding school system.

This report shows for the first time that, between 1819 and 1969, the United States operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states (or then territories), including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii. This report confirms that the United States directly targeted American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession. It identifies the Federal Indian boarding schools along with at least 53 burial sites for children across this system—with more site discoveries and data expected as the research is continued.

This investigation is a good first step in acknowledging the experiences of Federal Indian boarding school children. This report also highlights an opportunity for the United States to reorient Federal policies to support the revitalization of Tribal languages and cultural practices that the government attempted to systematically destroy over more than two centuries.

Native American Heritage Month is a great time to learn more about the history of the United States and the reality of the struggles, challenges, and accomplishments of Native Americans. Watch a documentary, read a book, research the history, visit an art gallery or a museum, or tour the Lewis and Clark Trail and celebrate the diverse and rich cultures, traditions, and great contributions of Native Americans!

For more information, go to https://www.usa.gov/tribes

Originally published on Omnigraphics.