I was talking to my mom recently about how long I’ve been an instructional designer. This past February marked a full year in my new position, and it feels simultaneously like just a few days and several years have passed since I made this career change. (Of course, this might just be how we all view time since March 2020.) After that conversation, I realized that, right at this moment, I’m in a great position. I have a master’s degree and about a third of a doctorate along with just over a year of practical experience in instructional design, yet I’m not so far removed that I’ve forgotten what it was like to be in the K12 classroom.

This seems like a good time to leverage the knowledge I’ve gained over the past several years into some instructional design tips for teachers.

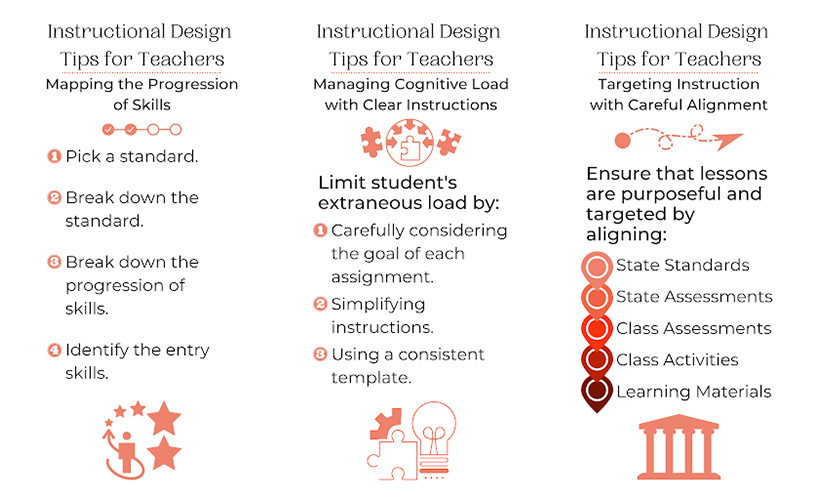

Mapping the Progression of Skills

One of the first things that I learned in my master’s program was to break down the progression of skills in learning. The whole thing was a tedious and lengthy process. We spent an entire 16-week semester going through the Dick & Carey model of instructional design to create a one-hour lesson. It was overkill for sure, but it was exactly the kind of overkill that was necessary. I consider it the same as when pre-service teachers write lengthy lesson plans. I remember creating a 30-page document to plan a one-week unit when I was an undergraduate pre-service teacher.

The goal of those lengthy lesson plans and the goal of my 57-page design document was not the document itself. The goal is in training your brain to think through each tiny step in the process so that you can do it automatically without the pages upon pages of description and justification.

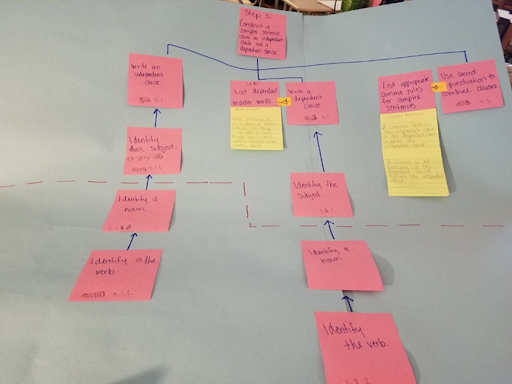

One of the most impactful activities in that semester was when I used post-it notes to break down the skills that students would need in order to correctly identify and construct all four types of sentences (simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex). I knew what the students needed to be able to do at the end of the lesson: identify and construct sentences. But how do I get them to that point?

I considered every skill that students needed to have in order to identify and construct all types of sentences. They needed to know independent and dependent clauses and how they combine into the four types of sentences. They needed to know the parts of an independent clause, which means they needed to be able to identify nouns and verbs. I wrote out each of these on post-it notes to map out the progression of skills, starting with what I could assume they already knew before the lesson and moving on to what they needed to learn next and next and next until they could master the objective. Using post-it notes allowed me to easily move the skills around until I had the correct progression.

This process taught me a lot about breaking down skills, and I took all of that into my teaching. I know that no teachers have the time to go through this whole process for every standard that we teach—it’s simply not feasible. But going through the process for one or two standards can help you to train your brain to think about the skills that go into each standard.

Pick a standard.

Whether you’re using the Common Core State Standards or Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) or other state standards, the standards dictate what students need to learn. What is it that the standard says a student needs to be able to do at the end of that lesson?

Break down the standard.

If your standards are anything like the ones here in Texas, each one is jam packed full of skills. Break it down. Are there separate skills that need to be addressed? What exactly is it that the student is expected to do? How will they be assessed on this standard?

Break down the progression of skills.

What do the students need to be able to do before they can do what the standard says? In my opinion, this is the most important part. If I jump straight to teaching my students compound-complex sentences before first teaching them what an independent clause is, I’m setting us all up for failure. Often the skill progression goes beyond what the standard says. Clauses are not mentioned in the original goal of constructing sentences, but it’s an important step that cannot be skipped.

Identify the entry skills.

Entry skills are the things that you can assume that your students already know before they come into the lesson. These could be things that they’ve learned in previous lessons or even previous classes. I know from experience that things can get tricky here. Sometimes we know that our students were taught a certain skill the year before or even the week before, but they don’t remember it now. Even though we identify it as an entry skill, it may still need to be refreshed before teaching the new content.

Managing Cognitive Load with Clear Instructions

One of the most useful things that I’ve learned has been the cognitive load theory, which originated in the 1980s. Without getting too technical, here’s a brief overview of the three types of cognitive load:

- Intrinsic load is the brain power required to learn a concept. Put simply, this has to do with how difficult a concept is for a student.

- Germane load has to do with the brain integrating new information.

- Extraneous load is all the distractions. This has to do with the way that new information is presented to students.

I could talk at length about these different types of cognitive load and how to utilize knowledge of each to enhance learning. However, for today, I just want to talk about extraneous load. Too often, we overload our students with information or instructions to the point where they are using all of their available brain power to figure out what we want them to do and they have nothing left when it comes to actually doing it.

I need to carefully consider the goal of each assignment so that I can design the assignment so that the majority of my students’ brainpower is focused on that goal. For example, if I need my students to identify figurative language in a poem, I want them to spend as much of their cognitive load on identifying figurative language in a poem and as little on figuring out the instructions.

Cognitive overload instructions: Use your iPad to go to a search engine and find a poem that meets the requirements, then copy that poem into a Google Doc. Create a color coded key of figurative language. Highlight the figurative language in the poem in the Google Doc according to that key.

Whew. That’s exhausting. By the time they find a poem that meets whatever the requirements are, they’re tired. Then they have to figure out how to copy and paste on an iPad? I’ll be lucky if they get that far.

There are a lot of ways that I can eliminate some of that extraneous load.

- I could give them a poem, or even a selection of poems, instead of having the entire internet to search. Often having too much choice is worse than having no choice at all.

- I can have the color-coded key already set for them. This simplifies the process for the students and for me when it comes to grading. Students won’t spend half of the class period choosing the perfect colors, and I can grade faster because every assignment uses the same color code.

- Sometimes just having consistent classroom practices can help to eliminate extraneous load. If they are copying and pasting into a Google Doc frequently in class, they can become comfortable enough with that skill such that it is no longer a strain on their brain. On the other hand, if they use Google Docs one day and Microsoft Word the next, they can easily get overloaded.

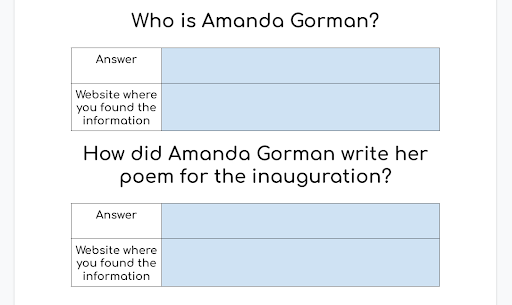

One strategy that I used to help eliminate extraneous load was using Google Doc templates. I used Google Classroom for my assignments, and it has this great feature where I can attach a Google Doc to the assignment and select the option to “Make a copy for each student.” This automatically creates a copy of the Google Doc for each student. It has their names in the title of the Doc, and it’s already attached to their assignments. They don’t have to remember to add their names (a true struggle) and they don’t have to spend 20 minutes of class time trying to figure out how to attach their work to the assignment and turn it in. Those seem like simple things, but for my eighth graders, it was a huge relief on their extraneous load. And honestly, it’s a relief on mine, too, because I can focus my own cognitive load on helping students understand the content.

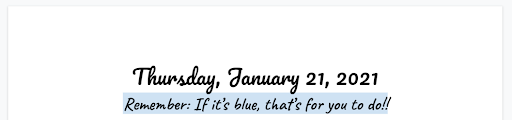

I took it another step further by setting up those documents to make it as clear and easy as possible for students to understand exactly what they needed to do. I used tables to set up the documents, and I shaded each box that students needed to complete in blue.

The top of each document always looked the same; consistency is huge when it comes to eliminating extraneous load.

Questions or instructions were in the white boxes, and students put their answers in the blue boxes.

This simplified the process for students. The questions are huge and difficult to miss. They knew immediately that they needed to provide both an answer and the website where they found that answer. Setting it up like this allowed them to focus on one box at a time.

Click here for a copy of this full lesson Google Doc.

I used Google Classroom and Google Docs because I first developed this system when we shifted to emergency remote teaching. This format works just as well on paper. It’s as simple as giving students a handout like this that gives them clear and specific instructions and makes it very obvious what they need to do and where, rather than just putting a list of instructions on the board and asking students to write on a piece of notebook paper.

Anything you can do to simplify the instructions means that students are spending less time figuring out what to do and more time on the actual skill.

Targeting Instruction with Careful Alignment

The last concept I want to discuss is alignment. This has become a bigger part of my day-to-day since I’ve started using the Quality Matters rubric for higher education, but it’s just as important in K12 instruction.

The basic idea is that everything in a course, from the assessments to the activities to the materials, should align directly with the objectives of the course. This helps us ensure that every lesson is purposeful and targeted. In the world of K12, we are beholden to the state standards. When I taught eighth grade English, everything I taught needed to align with the eighth grade English Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS).

It’s really easy to say, “Of course everything I do aligns to the standards!” but I would bet that, if you really looked closely at every lesson, you’d probably find some assignments or lessons that don’t align as well as you thought.

The key to ensuring alignment is to really know the standards and what they’re asking. Often, the standards aren’t written as clearly as we’d like, and when that happens, it’s important to have in-depth discussions with your teaching or curriculum team to develop a deep understanding of what the students need to be able to do. Look at the standardized assessments. For me, it was the STAAR test, and I spent a lot of time digging into the released tests and looking at the specific TEKS that were aligned to each question. It was sometimes surprising the way that the state assessed a certain TEKS because it wasn’t necessarily the way that I would assess it.

This is where things get dangerously close to sounding like “teaching to the test,” so let me take a moment to very clearly and specifically say that I am not advocating for teaching to the test. I’m advocating for teaching to the curriculum. Understanding the test and the standards is essential to being able to truly teach the curriculum.

As a former English teacher, I feel comfortable saying that we are probably the worst when it comes to alignment. I wanted to be an English teacher because I love books, I love reading, I love writing, and I wanted to share that passion with my students. It is oh so easy to get lost in teaching a great book and lose sight of the goal. It would be great if I could’ve had a book club style classroom where we talk about great books, but I needed to focus on the specific skills that the state of Texas says eighth grade students needed to learn. We could still have great discussions about books (I do miss the days of holding Socratic seminars with my stuffed alpaca “talking stick”); I just have to make sure that those discussions are targeted to the eighth grade TEKS.

If it were up to me, every K12 teaching team would have an instructional designer to help lessen the load of planning, but until the day that budgets truly reflect how much goes into educating our youth, hopefully these couple of tips will help you design your lessons.

See also:

- FREE Webinar: De-Siloing K–12 Schools: Maximizing Partnerships and Resources to Enhance Curriculum Development

- Why I Love the Flipped-Classroom Model

- 5 Instructional Design Models and How They Work

- 9 Trends in Instructional Design That Are Here to Stay

- A Guide to Instructional Design in eLearning

- Once a Teacher, Always a Teacher