From Course Scaffolding to the Flipped Classroom: Asynchronous Learning in Practice

Asynchronous learning offers many benefits to students and instructors alike. For students, asynchronous learning opens up opportunities to take classes regardless of restrictions like timezones or location. Faculty can use strategies for asynchronous instruction, such as the “flipped classroom” approach, to maximize live class time. Even before the pandemic, institutions offered distance education for degree programs, certifications, and personal growth. Here we’ll discuss how you can leverage tools for asynchronous learning to improve the student and faculty experience.

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Learning

Synchronous learning takes place when the learner and instructor are interacting in real time, such as during a live online class session or a face-to-face meeting. During a synchronous session, students benefit from the immediacy of interpersonal interactions and feedback from their instructors. There are also natural opportunities for spontaneous discussion about the class topic. For some students, additional support is required to adapt to the pace and participation expectations of synchronous learning.

Asynchronous learning, on the other hand, allows students to learn outside of the direct, real-time supervision of the instructor. Students are encouraged to complete readings and assignments at their own pace within a structured online space. For example, students with young children could complete a fully asynchronous first aid certificate course at their own pace while managing a busy family life. Flexibility is a major benefit of asynchronous learning, especially for students whose learning needs or responsibilities outside of class make in-person learning challenging.

Applications of Asynchronous Learning

Faculty can also benefit from the flexibility afforded by asynchronous learning. Most notably, asynchronous instruction allows for more time in the virtual or in-person classroom to facilitate discussion or hands-on activities.

Pre-Session Instruction

Asynchronous learning lends itself especially well to pre-session preparation. Students may be assigned to watch a video or complete a tutorial that presents much of what an instructor might cover in the “lecture” portion of a class. Then they come to class with a baseline of knowledge that allows the instructor to focus more on addressing student questions, focusing on the most complex concepts, and allowing for practice time during class. This “flipped classroom” approach allows for hands-on, high-impact learning when students come to class without sacrificing content coverage. Credo’s Information Literacy product is a great resource to use for this type of work. If you’re teaching a class like Composition 101 or any class where you might be assigning a research paper, you might assign one of the product’s videos on source evaluation or search techniques to give students exposure to these concepts. This allows students to absorb and apply the information beforehand and develop questions to ask you during the live session. Further, you can benchmark students’ grasp of the content and adjust the goals of the live session as needed.

Course Scaffolding

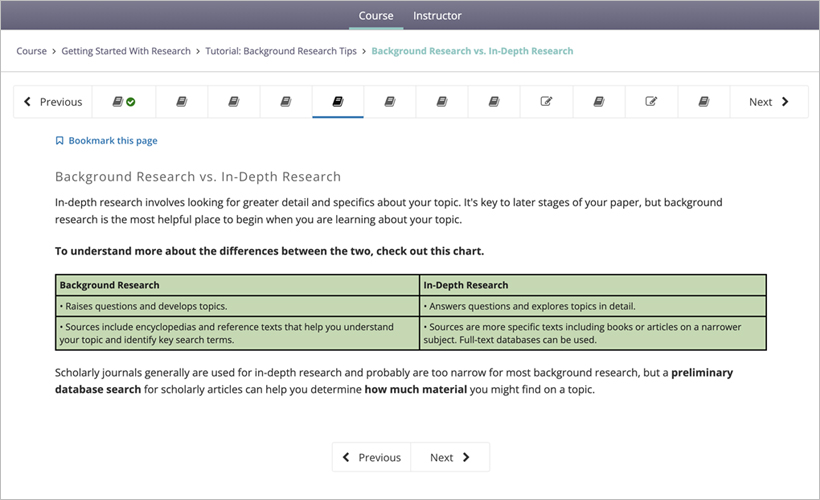

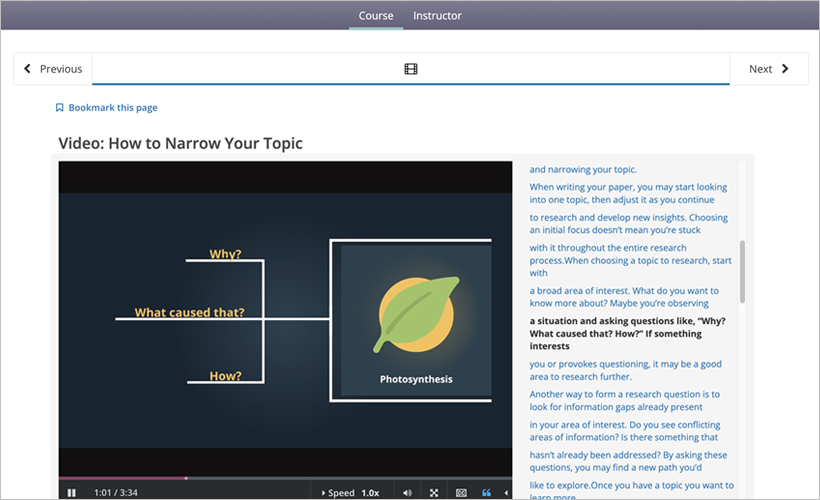

Are you concerned about having enough time to cover your course’s content and incorporate basic skills like writing a research paper into your syllabus? Making use of multimedia to flip instruction throughout several weeks of your course allows students to learn basic concepts and practice research skills on their own time. For example, if you’ve assigned students a research paper but they need more support on aspects of the research process, Credo’s Information Literacy – Core materials could be assigned to scaffold each step of the process, as appropriate. These resources could include content like the Background Research or Narrowing a Topic tutorials at the beginning of the research process, or more specific guidance on source types or evaluation during in-depth research. Relevant multimedia can be shared with students at each step of a major research project.

Remediation

Sometimes, students need extra time or resources to fully grasp a topic. Asynchronous learning platforms can be used to house supplemental materials that can be assigned to students to reinforce their understanding of a concept or strategy. For example, it can be hard to balance teaching students the conceptual knowledge they need and the basic mechanics of researching and writing required for an assignment. Credo’s Information Literacy – Core materials may be used as a remedial tool to allow students who need to review basic skills to get the help they need without significantly impacting your course syllabus. Specific materials might include the tutorials How to Read Scholarly Materials or Search as Exploration.

Features of an Effective Asynchronous Learning Experience

Modular Learning and Customization

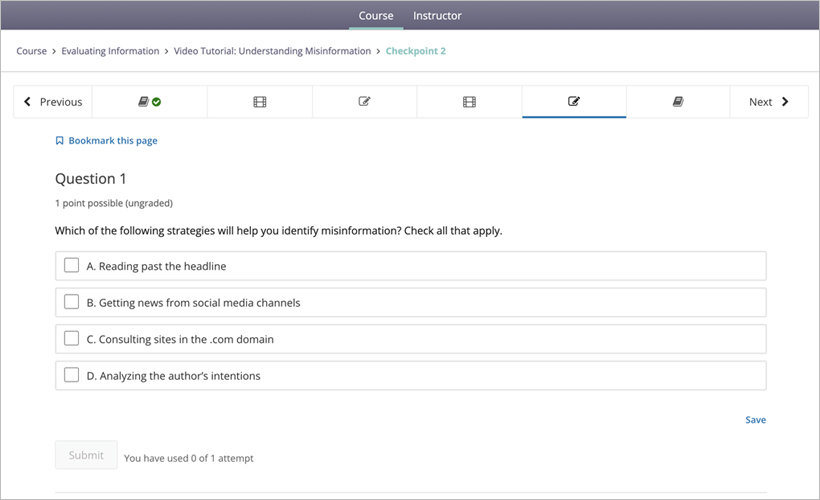

Unlike traditional reading assignments, effective asynchronous course materials are designed as modules, or chunks, of related content. Breaking up content into manageable sections works within the attention span of online learners, which can be limited to six minutes at a time. One way to maximize the time students spend with asynchronous materials is to use a variety of information formats. With student needs and learning habits in mind, Credo’s Information Literacy course delivers information through a mix of text, video, and infographics and tests students’ knowledge through different types of assessments. Further, the Credo platform was consciously designed with intuitive navigation in order to reduce unnecessary cognitive load.

With Credo’s Information Literacy, instructors can customize the order and release of content to better support their students’ needs. Instructors can also add content such as links to course-specific LibGuides.

Assessment and Reporting

One of the downsides of learning outside of the classroom is the lack of opportunities to immediately assess students’ understanding of concepts presented in the session. In an effective asynchronous course, the lack of real-time assessment and discussion is replaced by self-paced assessments and activities in which students demonstrate their knowledge. This method of spaced retrieval learning helps students reinforce their understanding of concepts and skills presented in each module.

Credo’s Information Literacy – Core includes a pre- and post-test that instructors can use to benchmark student performance. The Insights reporting feature helps instructors analyze student scores, engagement with content, open-response prompts, and activities. In addition, the reporting feature allows instructors to identify and organize content based on specific learning outcomes that align to standards such as the Association of College & Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy or the American Association of Colleges and Universities’ VALUE Rubrics.

Sources:

Kaempf, Sebastian. 2022. “Getting Our Teaching ‘Future Ready’.” In Pandemic Pedagogy: Teaching International Relations Amid COVID-19, edited by Andrew A. Szarejko, 189-202. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83557-6_12.

McQuaid, John W. 2010. “Using Cognitive Load to Evaluate Participation and Design of an Asynchronous Course.” The American Journal of Distance Education 24, no. 4: 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2010.519949.

Polat, Haka and Songül Karabatak. 2021. “Effect of Flipped Classroom Model on Academic Achievement, Academic Satisfaction and General Belongingness.” Learning Environment Research 25: 159-182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09355-0.

About the Authors

Devon Lee began her work in the field of information literacy with Credo Reference in 2016. Developing tutorials, videos, and assessments for the Credo Information Literacy products has given her the opportunity to dive deep into topics from evidence-based practice to digital citizenship. She has a B.A. in History from the University of California, Davis, and a Masters in Library and Information Science from San Jose State University.

Tamar Rubin was the Manager of Learning Design at Credo, an Infobase Company, where she has worked for six years as a designer of information literacy content for libraries. She has an MSLIS from the University of Illinois and a BA in history from Yale University.