Differentiated Learning: How Databases Can Help

As any teacher can tell you, one foundation of creating lesson plans is considering your students’ individual needs—in other words, strategies teachers use to differentiate the delivery of content. This consideration requires obtaining a certain amount of knowledge about their students, which often leads teachers to administering surveys. Insert the likelihood of a discussion of learning styles and multiple intelligences. I remember stressing out on a few occasions as I tried to incorporate kinesthetic learning into my high school English classroom.

Last year, the faculty at my school read Dan Willingham’s book Why Don’t Students Like School? and he visited our school for discussions. In particular, we found a lot to discuss as we read Willingham’s chapter on debunking the multiple intelligences theory, “How Should I Adjust My Teaching for Different Types of Learners?”

Rethinking how we consider student learning styles when planning instruction has strong implications for student achievement.

Rethinking how we consider student learning styles when planning instruction has strong implications for student achievement.

For example, Willingham discusses the difference between learning styles (how we prefer to think and learn) and learning abilities (capacity for and level of learning), which are not the same (169). It is also difficult to show evidence of the idea that one particular learning style “is stable within an individual” (170), which is where I think some teachers get stuck. If you think a student is an auditory learner, that doesn’t imply the student should only be given auditory learning experiences. Landrum suggests considering individual needs that are instructionally relevant instead of blindly espousing the idea of learning styles as consistently relevant instructional variables (13). As Willingham discusses, delivery of material should match the content, not a learning style.

Here’s an easy example. When one United States History teacher was planning a unit on the Progressive Era, the standards included learning about the development and impact of labor unions. It was a natural choice for me to include not only articles describing some events that prompted the creation of labor unions, but also photographs, songs, and documentary clips of people who experienced the events. It doesn’t make pedagogical sense to simply tell students about songs or people when you can utilize other media formats.

The above example also illustrates differentiated instruction. On ISTE’s blog, Dale Base distinguishes among differentiated, individualized, and personalized learning. Most relevant to our discussion here is to keep in mind that differentiated instruction keeps in place the same overarching academic goals for all students. I needed to assess if students could explain the development and impact of labor unions during the Progressive Era. To reach that goal, they could use learning from any combination of the sources I provided.

How Databases Can Help with Differentiated Instruction

There are other instructional strategies teachers and school librarians can use when planning differentiated instruction—in particular, what databases offer.

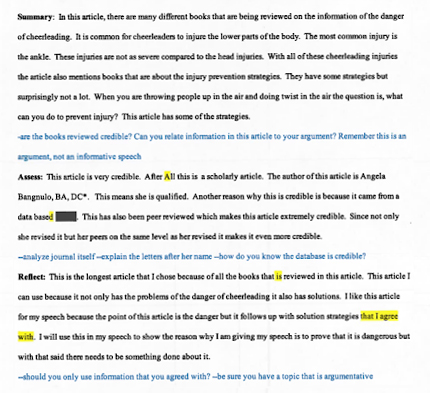

I was helping a public speaking teacher implement her researched argumentative speech unit when I was applying for National Board certification in Library Media, part of which requires evidence of differentiation. All students were working toward the same goal: produce an effective, well-researched argumentative speech. But the path toward reaching that goal could consist of any number of strategies. Landrum writes that teachers can differentiate by providing varied levels of difficulty, varied degrees of scaffolding, and a variety of ways for students to work (9).

I guided one student to use an eBook because I knew he could take notes in the eBook and then transfer the notes to a Google Doc. The eBook was an effective choice because he needed more scaffolding with reading based on his own self-evaluation. Then I was able to guide his progress since it was a shared Google Doc.

Using this strategy to find a source, take notes, evaluate, and reflect made the student’s thinking visible so I could provide scaffolding at appropriate points.

During the same project, I taught one student to use a database for academic libraries (provided by my state library) because she needed a peer-reviewed, academic publication written on a higher level. As you can see, this student achieved the same academic goal as the previous student but utilized a different source of information.

You can see that the students reached the same academic goal: create a persuasive speech using credible research. I was able to help individual students determine which research methods and materials fit their specific needs. It is important for teachers and librarians to embrace this possibility instead of thinking that all student learning should look the same or proceed in the same way. For this particular academic goal, there are numerous acceptable and effective ways to demonstrate learning.

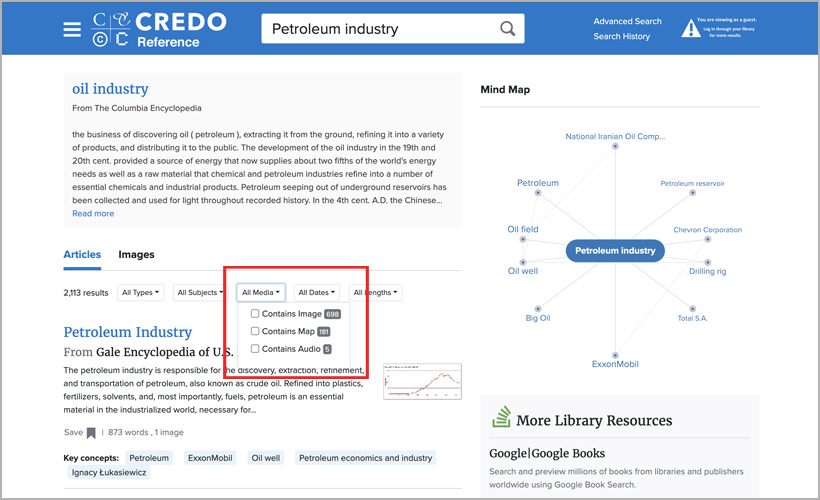

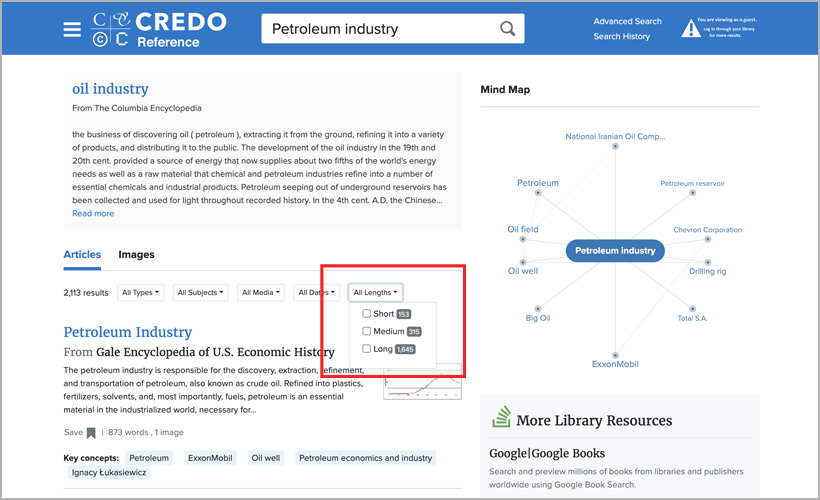

Databases offer a variety of features to help teachers and librarians implement differentiated instruction. Users can limit results in Credo Reference by type of media. It’s also possible to limit results by length of article. While school librarians do not recommend that students be limited to their Lexile levels while engaging in recreational reading, it can be useful when planning classroom instruction so that students are appropriately challenged.

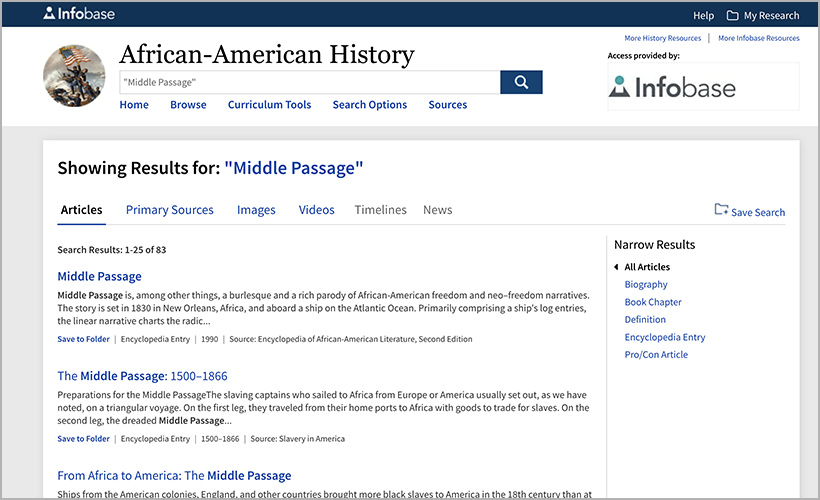

Before asking students to browse entire databases for a specific assignment, consider limiting which type of information they should seek. Would it satisfy the learning goal to use shorter reference articles from Credo Reference, primary sources from African-American History, or critical articles from Bloom’s Literature? Databases make it possible for teachers and librarians to differentiate instruction by dividing students into groups to seek a variety of information sources.

In the screenshot below from the African-American History database, the articles could be used to scaffold or supplement information gleaned from textbooks or a teacher’s lecture. Some students might benefit from a definition or encyclopedia entry article to support learning while others may be ready to move on to considering a pro/con article. Each student could be assigned a topic and create a project showing analysis of a primary source, definition, image, and map, giving students multiple opportunities to encounter information in a variety of formats to show learning.

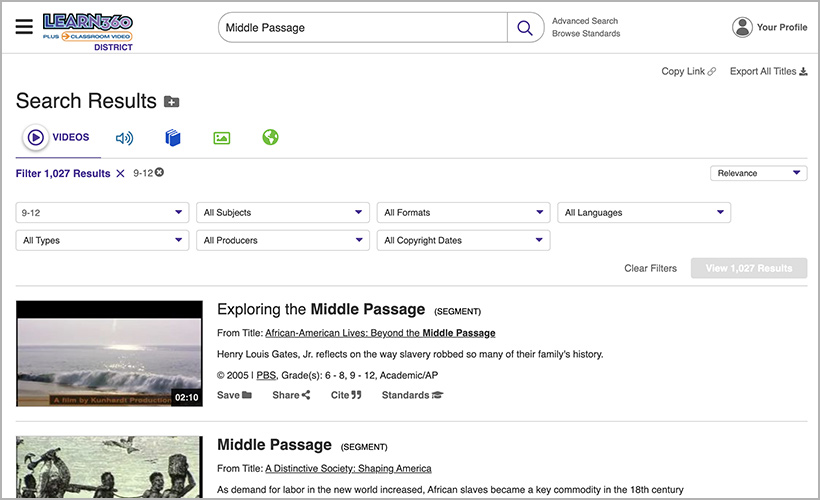

Continuing this example, the teacher could create a playlist of videos from Learn360 to help supplement learning about the Middle Passage. I searched “middle passage” and limited the results to grades 9–12. I could have further limited my search by which type of information source (e.g. documentary film, educational video, images, language, etc.). Students could watch a video and take notes instead of relying on textbook reading or a teacher’s lecture, depending on their individual learning needs. The overall academic goal remains the same for all students, but providing various paths for encountering the information constitutes one example of differentiation.

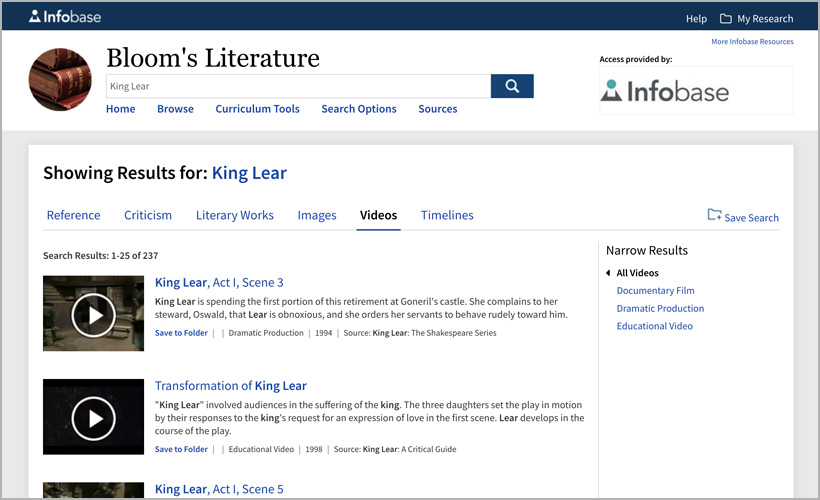

For students who may need extra support in literature classes, have the school librarian show students what’s available in the Bloom’s Literature database. It may be helpful to access the videos which could be utilized by a student throughout the reading process. Asking students to contrast dramatic interpretations of the text they’ve just read can help reinforce learning and encourage deeper learning, especially by giving students additional opportunities to encounter the text and to demonstrate learning.

It’s important for teachers and librarians to learn about more recent theories related to learning styles and learning capabilities when planning instruction. Doing so allows us to move forward with effective differentiation strategies by utilizing resources already at our fingertips.

References:

Basye, Dale. (2018, Jan 24). “Personalized vs. differentiated vs. individualized learning.” ISTE. https://www.iste.org/explore/Education-leadership/Personalized-vs.-differentiated-vs.-individualized-learning

Landrum, Timothy J. & McDuffie, Kimberly A. (2010). Learning Styles in the Age of Differentiated Instruction. Exceptionality, 18(1), 6-17. DOI: 10.1080/09362830903462441

Wai, Jonathan (2020, October 28). Are There Really Multiple Intelligences? Debunking myths about human intelligence. Psychology Today. Retrieved 5 February 2023, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/finding-the-next-einstein/202010/are-there-really-multiple-intelligences.

Willingham, Daniel T. (2006, June 30). Reframing the Mind. Education Next. Retrieved 5 February 2023, from https://www.educationnext.org/reframing-the-mind/